This game further cemented my belief that I do not want to use assembler for any serious project.

- Alpatron, reviewing Human Resource Machine

In this post, I will demonstrate how to use Compiler Explorer as a high-level IDE for creating solution designs for the assembly-level programming game Human Resource machine.

What’s going on here?

Compiler Explorer is an easy to use tool for viewing the assembly output for C/C++ code. It has many convenient features over generating assembly yourself, such as color highlighting of matching sections, filtering out noisy boilerplate code, and instant dropdown selection of different target architectures.

I was inspired to use Compiler Explorer after watching Jason Turner make frequent use of it in his C++ Weekly episodes. However, it was a bit dumbfounding to come up with a motivating use case for generating examples.

Then I remembered picking up the game Human Resource Machine, which uses the setting of computers-as-people office drudgery as a way to stealthily introduce assembly language concepts.

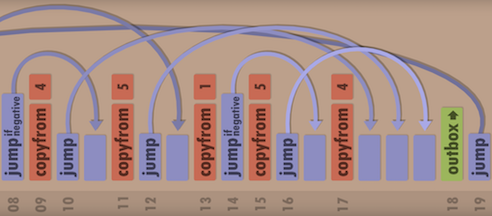

For the early levels, the challenges are easy to tackle and the actions of the little office-drone/accumulator-register are easy to understand. This simplicity of the actions later becomes a hinderance, as the challenges become more unmanageable due to your limited expressive options. Eventually, the complexity of the algorithms requested leads to jump diagrams that literally look like interlaced spaghetti.

The idea suddenly struck me to use GCC assembly output as a way to solve the problems of Human Resource Machine in a higher level language. This effort would provide concrete exercises to play with in Compiler Explorer, while also simplifying the task of organizing confusing jump spaghetti in the game.

Proof of concept

To evaluate the feasibility of this project, I went straight for a problem that I abandoned earlier, due to the confusion with the jump instructions. Level 17, Exclusive Lounge, asks that for two numbers coming from the inbox:

- Send a 0 to outbox if they have the same sign.

- Or send a 1 to the outbox if their signs are different.

Not an intellectually stimulating problem, but manually directing the jumps was quite the confusing chore! In my defense, I think the level designer acknowledges the complexity of the task, as the level sits on an optional challenge branch.

After loading Compiler Explorer, I came up with some quick C code for the solution:

int Exclusive_Lounge(int x, int y) {

if (x < 0)

{

if (y < 0) return 0;

else return 1;

}

else // x >= 0

{

if (y < 0) return 1;

else return 0;

}

}… which resulted in the following assembly output:

Exclusive_Lounge(int, int):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], edi

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], esi

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 0

jns .L2

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 0

jns .L3

mov eax, 0

jmp .L4

.L3:

mov eax, 1

jmp .L4

.L2:

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 0

jns .L5

mov eax, 1

jmp .L4

.L5:

mov eax, 0

.L4:

pop rbp

retThe first wrinkle was with the jns instruction. Originally I was attempting to target the “jump if negative” instruction in HRM, but the opposite operation was generated from comparisons driven by ‘<’. Changing the occurrences of < to >= led to the output of js as desired.

I also noticed that I could save a copyfrom instruction if my first action involved the last argument pushed to the stack. That meant starting the first comparison with argument y instead of x as above.

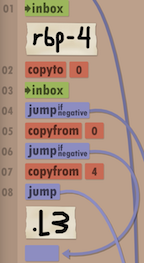

To aid in translation, I marked the assembly code with references to HRM instructions, and the HRM instructions with references to the generated x86 labels:

Exclusive_Lounge(int, int):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], edi ; _0 where '_' implies floor

; inbox

; copyto 0

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], esi ; _1 arg not used again,

; directly hold from inbox

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 0 ; _1 already in hand

js .L2 ; jump if negative

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 0 ; grab _0 from floor

js .L3 ; jump if negative

mov eax, 0 ; _4 = 0

jmp .L4

.L3:

mov eax, 1 ; _5 = 1

jmp .L4

.L2:

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 0 ; _0

js .L5 ; JIN .L5

mov eax, 1 ; _5

jmp .L4

.L5:

mov eax, 0 ; _4

.L4:

pop rbp ; outbox

ret ; jump to beginningThoughts on the process

Suffice to say, the ‘;’ comment system in assembly was so much more convenient than the initially-cute but impatience-inducing mouse-written tape notes in HRM.

Running the program didn’t satisfy the efficiency targets for instructions or cycles, but it was incredibly gratifying to easily solve a problem previously stymied by jump spaghetti.

One disappointment was that I could not use the -O settings to automatically generate optimized code, as the tricky use of esoteric x86 instructions made the optimized output less ready for translation. If any efficiency gains were to be had, they would need to be discovered by human intuition.

Building more abstractions with C macros

Another benefit from editing C in Compiler Explorer was to enable the use of very crude subroutines, defined by C macros. Using function calls in the C code would not work well in HRM, as the overhead of pushing/popping arguments on the floor as a crude stack would be a hinderance to translate.

For example, HRM does not have an operation for comparing two variables directly, as jump comparisons are only against 0 and the value in hand. In Level 14, Maximization Room, you can use subtraction as a workaround for comparing two values a and b, returning the greater of the two:

int Maximization_Room(int a, int b)

{

if ((b - a) >= 0) return b;

else return a;

}With C macros, you can have the illusion of a function call, without the overhead of pushing to an imaginary stack:

#define MAX(a,b) ((b - a) >= 0) ? b : a;

int Maximization_Room(int a, int b)

{

return MAX(a,b);

}… with x86 code that neatly organizes the resulting order of jump instructions:

Maximization_Room(int, int):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], edi ; _0

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], esi ; _1

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8] ; _1 ignore, already in hand

sub eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-4] ; _0

test eax, eax

js .L2 ; jump if negative

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8] ; _1

jmp .L4

.L2:

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-4] ; _0

.L4:

pop rbp ; outbox

retTracking pre-populated floor tiles

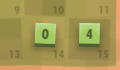

Sometimes a level will provide constants that you can use from the floor:

You can define local variables to generate register offsets that you can track throughout the assembly program:

int ZERO = 0; // _14

int DIMENSION = 4; // _15mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 0 ; annotate every occurrence of this offset as floor _14

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-12], 4 ; ditto, annotate as floor _15

; ...

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8] ; now you know to copyfrom floor tile _14Multi-line macros with multiple inputs/outputs

With help of the local variable annotation trick above, you can define macros that manipulate multiple inputs and outputs:

// without stack pushing/popping, changes to all the args will persist

#define multi_func(arg0, arg1, out2, out3) { \

arg0 += 1; \

out2 = arg0 + arg1; \

out3 = out2 -= 1; \

}

int main (void) {

int your_out2 = 42; // In HRM, you can ignore the silly values but

int your_out3 = 1337; // they can help identify the offset locations in the assembly

int arg0_also_mutated = 1;

multi_func(arg0_also_mutated, 2, your_out3, your_out4);

// Use your_out# variables, either as outbox items or for more calculations

}Careful: note that the first 2 args are also mutated if you kept their variable references, so beware of side effects on all your macro inputs.

For example, I used this trick to save the division and modulus results from a macro subroutine when solving Level 39, Re-Coordinator.

Abstractions as a design tool

While I wouldn’t joke that these sort of shenanigans are preparing me to understand the immensity of x86, this exercise really honed in the fact that abstractions matter, and that the right tooling can make mentally challenging tasks much more tractable!